|

| Jayden Gonzales, seen here when a Plowboy, is now a track star at McMurry. |

And ex-Plowboy Jayden Gonzales, now a freshman at McMurry, broke his personal record in the men’s pole vault with a vault of 14’ 9½” at the Matador Qualifier in Lubbock Friday. He currently ranks third in the region and in the Top 50 nationally.

Both the Plowboy and Plowgirl track teams open their seasons tomorrow at the Big Spring Howard County Invitational Meet at Blankenship Field in Big Spring. Other participating teams are from Ackerly Sands, Big Spring, Coahoma, Colorado City, Compass Academy, O’Donnell, Forsan, Garden City, Iraan, Loop, Midland Greenwood, Midland Texas Leadership, Grape Creek, Slaton, Stanton, Wall, Whiteface and Wink. The meet begins at noon.

Junior High boys and girls open their track season at the Wolfpack Relays in Colorado City on Friday afternoon starting at 2:30pm.

--o--

NEW P-TECH VIDEO INTERVIEWS STUDENTS WORKING ON BACHELOR'S DEGREES IN ROSCOEPRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY ELECTION DAY IS TUESDAY

Election Day for voting in the Presidential Primary in Texas is this coming Tuesday, March 3, with both Republicans and Democrats expecting a large turnout. In Roscoe, voting will take place at Fellowship Hall in the First Baptist Church on 401 Main Street from 7:00am-7:00pm.

For more information about the election and to check your eligibility to vote, click here.

--o--

ROSCOE IN YEARS GONE BY: THE DROUGHT OF 1917-18

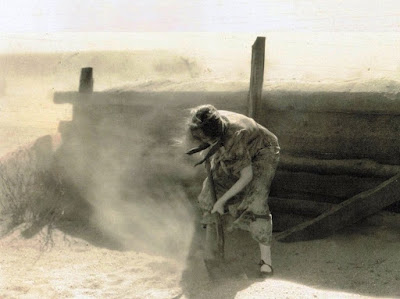

|

| Lillian Gish battles a West Texas drought in the 1928 movie The Wind. |

For the people of Roscoe, the drought wiped out the prosperity, gains, and optimism of the previous years and reminded them that life’s blessings can also be laced with setbacks that must be dealt with and endured. Many residents had to move their families away in order to survive. In others, the women and children stayed back while the men and boys found employment elsewhere and sent money home. Some young men went into the army, while others went to oil boom towns like Ranger in search of jobs. The city would begin to recover financially with good crops in 1919, but in some ways it would never regain its previous bloom.

1916 had ended on a high note for Roscoe with a successful Nolan County Fair and good crops in vegetables, grain, and cotton. The harvest was unimpeded by fall rains, and the winter was also dry. By the spring of 1917, drought conditions had developed, and cowmen and stock farmers “became alarmed and began to reduce their operations.” That spring no substantial moisture came, and farmers waited in vain for a rain that would allow them to plant.

In May, these words of encouragement appeared in the Roscoe Times:

Rain—*drouth (or drought) is one of those few words in English with two acceptable spellings, and both have been in use for centuries. Historically, if the word is pronounced at the end with a -th, then drouth should be used and if not, then drought. However, no one really pays attention to such details, and either spelling is acceptable, although consistency is preferred.

Now and then we hear of a man getting weak in the knees because of the continued drouth.* Some men haven’t the faith of a grain of mustard seed. This is no time to be discouraged. It rarely ever fails to rain 12 or 15 inches here between Christmas and Christmas. Most of this usually comes in the summer months.

If during the remainder of the year we get the least quota of rain usually allotted to us, we may yet make bumper crops. Who knows? Cheer up, gentlemen; throw away your grouch; don a smile—live happy.

Some dry-planted in hopes of a June rain that would bring up a crop but never got one—or if they did, July was very hot and dry, and conditions brought about a “sharp deterioration” of what little crop there was. According to more than one source, no cotton was ginned in Roscoe that year or the one that followed.

By October 26, the pep talk was gone, as the Roscoe Times now wrote,

We venture to say that not in 50 years will the crop failure in Nolan County be so complete again as it has been this year. An extensive drive over the entire county showed only a little feed on the Divide and Nolan communities and almost nothing elsewhere. It is a hard prospect, but we can take consolation in the fact that it is not likely to happen again soon.Unfortunately, it did happen again soon, and the following year, 1918, was no better than 1917 had been.

On September 23, 1983, the Roscoe Times published the following article that describes what life was like during those two years:

THE 1917-1918 DROUGHT

by Marion Truett Duncan

Very little has been written about the Roscoe drought years 1917-1918. I was only a boy then, but I can remember many things that happened. I want to say from the start that during the two drought years, the Roscoe country was like a desert. The wind blew most of the time out of the west, often blowing the dust on the ground with it. We had some bad sandstorms then. If anyone was away from the house and saw one of the sandstorms coming, they dropped everything to get to the house before it hit.Here are some additional drought-related remarks from Marion Duncan’s article, “Windmills.”

When the sandstorm hit, you couldn’t see more than a few feet ahead, and the sand would get in your eyes. If caught in one of the bad sandstorms and you had a team to a wagon or horse and buggy, you turned the lines on the reins loose and let the team find their way home as fast as they could. The wind blew the ground off the hard dirt and moved it to the fence rows, pastures, and any objects it could fall behind. The sky was filled with sand and dust when we had these storms. I remember one of the days during the drought, the sky had so much dust that we had to light the coal-oil lanterns to see to eat dinner. My home was built in 1945 on the old garden spot that wasn’t used during the drought. I believe the drought blow-dirt raised the level of the ground near two feet in that old garden site.

The old dirt road from Roscoe to Snyder had sand dunes and drifts on it all the way to Snyder. On some fence rows the blow dirt would cover the fences to the top of the fence post, and a horse could be ridden over the fence.

Although it was the worst drought on record for West Texas, the Roscoe windmills never stopped pumping plenty of good water. The freight and passenger trains never stopped running through Roscoe, and people kept their courage. Those who decided to stay stayed. In this article I have given much emphasis on the blowing wind and sand in a country that was at times in summer like a hot desert.

During the years of the drought almost all the men were gone. The young men went into the army of World War I. The older men left to find work so they could send money back home to their families. The neighbor women helped each other and stuck together like one big family, and they made it with their children through the drought. Most of the older women were early settlers and like the pioneer women they had the courage to see things through. I might add that I don’t ever remember anyone around who got sick from the sand or dirt.

In 1919, the big rains came back. Those who went away to find work came back. The war had ended and the soldiers were coming back. In that year a good crop was made with a good price, and it was the start for some good years instead.

It was during the drought years when we had our worst water problems. During the hot and dry summer months, the wind would often stop blowing, the windmills would often stop running, the stock tanks and creeks would dry up, and the clouds would pass over and not rain. The drought years were difficult years, and it was always hard to find water when you needed it.Here are a couple of excerpts about the drought from Roscoe family histories in The First 100 Years: Nolan County, Texas:

When our stock tank dried up, we would drive and lead our horses and mules to some place where there was water. We had a different problem with the cows. When we had to drive them very far, we found it was easier to haul water for them in wood barrels in a wagon. We poured the water out of the barrels into wash tubs or troughs, and the cows would drink all they could hold.

During these kinds of times, we always looked for rain clouds that might bring rain and enough wind to turn the windmill. I can remember when we used up all the water in the cistern, one of us would climb up the windmill ladder to the platform and turn the big wood wheel by hand and get enough drinking water for the family

I would like to write one other story about how the windmills were of help. During the West Texas drought of 1917-1918, there were people who left their homes to go places to find work. Some traveled by covered wagons. We lived on a cross-country road, and sometimes the wagons stopped at our place and the drivers would ask for water for their teams and for drinking water. It was the custom in those days to give anyone water who asked. The travelers carried small wood barrels on the side of their wagons. The barrels held from twelve to fifteen gallons of drinking water. They would water their teams and we would fill the barrel with water from our windmill or cistern. When traveling on the road, their teams would often need water. The wagons carried medium-size buckets, and the drivers would drain some of the water from the barrel into the bucket and the horses would drink from it.

Plunkett. Some years later R.R. built a huge barn and erected a windmill with a 16-foot wheel and two fan tails. The windmill pumped water into a large earthen tank. During the drought of 1917-18, sandstorms filled the tank with sand and covered up farm implements and fences, allowing the farm animals to roam freely.Also, when my brothers and I were kids, we heard stories about the drouth of 1917-1918. Here are three I remember:

Rannefeld. In 1917 and 1918 not a single bale of cotton was made due to the drought.

Rayburn. The next years, 1917 and 1918, were drought years. The fields around Roscoe turned into dust bowls. There were no crops and many of the men had to leave home in search of work. Henry Rayburn recalls travelling to Norfolk, Virginia, in 1918 to obtain work in the ship yards. The influenza epidemic was killing men by the thousands, and after his brother, Young F. Rayburn, died from the disease at Newport News, Virginia, Henry returned to Roscoe.

After a good crop in 1914, my grandfather decided it was time for the family to get an automobile, so he purchased a new Reo, a popular make in those days, and was proud of it because he was one of the first local farmers to own a car. However, when the rains never came in 1917 and no crops came up, that September he put the car in the shed, took the wheels off and put it up on blocks. Then he, his eldest daughter, and two older boys traveled in a mule-drawn covered wagon out to Pecos to pick cotton so the family would have enough money to make it through the winter. His wife stayed at home with a younger daughter and little son. As the covered wagon approached Big Spring, one of the boys, who was about 12, found a nickel in the road. A short while later as they passed through the town, they missed him and wondered where he went. Then they saw him returning to the wagon with an ice-cream cone, and his dad asked him where he got it. He said he bought it with the nickel he found, and for that he got a hard whipping.

Another was about Mancel Pointer, a young Roscoe farmer who was drafted into the army in the spring of 1917. It had not yet rained that spring, but he went ahead and dry-planted a field of wheat before entering the army, receiving his training, and going overseas. There he stayed until the spring of 1919, when he returned to the U.S. and received his discharge. During his welcome home, he asked family members how the wheat crop he’d planted in 1917 turned out, and family members told him to take a look out in the field. There had been no rain until just before he returned, and the wheat he had planted two years earlier was just coming up.

Another was a story my father told us that happened in the spring of 1919 when the rain finally came back. A couple of toddlers were playing outside in the dirt yard while their mother was busy in the house. All of a sudden, she was surprised by them running into the house screaming and crying. She couldn’t figure out what was wrong with them until she went outside and noticed that it had begun to sprinkle. The toddlers had no idea what the drops of water falling from the sky were because they had no memory of anything like that happening before.

I had planned to include more information, such as how the drought killed Roscoe’s Nolan County Fair, which was never held in Roscoe again but resumed in 1920 in Sweetwater, or how the drought caused a population loss in the area, or how Roscoe’s fate was shared in the Big Country and Panhandle with other farming and ranching communities, as well as other drought stories and news items, but I can see this has already gotten pretty long, so I will close it here.

In short, the 1917-1918 drought was one of those life-changing events that anyone who goes through never forgets and is never quite the same again afterwards.

--o--

WEATHER REPORT: MORE RAIN, WINTER WEATHER

|

| Monday morning's sunrise. |

Following the rain, temperatures were cool for the rest of the week with highs of 43°F on Thursday and 50° on Friday with lows of 30° and 25°. The weekend was a little warmer, but highs were hardly balmy at 62° on Saturday and 58° on Sunday. The high for the week came on Monday, when the afternoon temperature reached 68°, but the warmth all came to a halt on Monday night as a norther blew in with howling wind and cooler temperatures. Yesterday’s high dropped to 52°.

The outlook is for cool and sunny weather today with a high of only 47° and continued strong north wind. However, that will all change tomorrow as the wind shifts to the southwest and temperatures rise. The high should reach 63° tomorrow and 67° Friday, followed by springlike weekend weather with highs in the seventies, 71° on Saturday, 77° on Sunday, and 73° on Monday. Lows will also be warmer at 41° Friday, 49° Saturday, and 55° on Sunday.

Any rain is unlikely before Tuesday, when there will be a 40% chance of precipitation. At least that’s the chance they’re giving us at this time.

--o--

† ELNOR GLYNN FREEMAN

Funeral services for Elnor Glynn Freeman, 88, of Roscoe were held on Saturday, February 22, at 10:30am at Roscoe Church of Christ with Rian Freeman officiating. Interment followed at Roscoe Cemetery. She passed away on Thursday, February 20.

Elnor was born in Lamesa on March 7, 1931, to Homer and Gertrude McLeod and moved to Roscoe when she was 9 years old. She graduated from Roscoe High School when she was 16, then attended and graduated from Abilene Christian University. She married Jerland Fred Freeman on December 18, 1949, in Roscoe. She was a member of Roscoe Church of Christ for over 80 years and taught vacation bible school for many years. She was a Roscoe Plowboys fan and loved watching football. She worked at KXOX and was a member of the garden club. In 1975, she started a tradition of Sunday lunch, where family and friends would come by, and carried it through last Sunday. She loved to cook and was a devoted wife, mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother.

Elnor is survived by her daughter, Pat Hagerman and husband Steve of Roscoe, Jeanetta Monday and husband Douglas of Shelbyville, Indiana; sons, Don Freeman of Roscoe and Steve Freeman and wife Jani of Brownwood; 16 grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren; sister, Robbie Ratliff of Brownwood; brother Wade McLeod and wife Judy of Round Rock; daughter-in-law Linda Freeman of Colorado City; son-in-law, Edwin Teltschik of Sinton; and numerous nieces, nephews, and cousins.

Elnor was preceded in death by her husband, Jerland Freeman (2011); parents, Homer and Gertrude McLeod; son, Freddy Freeman (2007); daughter, Terri Jo Teltschik; grandson, Chris Hagerman (2017); great-grandson, Devon Reece Freeman (2015); and sisters, Betsy Scott (2015) and Mary Jo Cardwell (1988).

Pallbearers were her grandsons and granddaughters and honorary pallbearers were her great-grandchildren.

--o--

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete